Why did Dallas grow North?

August 8, 2017 | Posted in: Business, Commercial Real Estate, Economics, Real Estate

It is no surprise that Dallas gets hot in the summer—the Dallas Morning News is reporting that Dallas is expected to bake in temperatures as high as 110ºF early next week— and when the city of Dallas starts to scorch, so does the rest of the metroplex. However, back in 1907, a few Dallas suburbs apparently defied the laws of meteorology. In 1906, Dallas developer John Armstrong bought the land that would later become the city of Highland Park and just a year later, began to promote it as a retreat “beyond the city’s dust and smoke.” In fact, according to its slogan: “It’s (or maybe was) Ten Degrees Cooler in Highland Park.” Despite the best efforts of Mr. Armstrong to emphasize his enclave’s cool, alluring mystique using slogans, real estate in Highland Park has only become hotter over the past century—Sam Wyly just sold a home there for approximately $12.5 million.

Part of the reason that Highland Park became such a valuable neighborhood in the succeeding years lies in its unique history. Unlike similar suburbs of Dallas like Oak Cliff, a similarly “elite residential area” also developed by Armstrong, Highland Park was never annexed by the city of Dallas. Although Oak Cliff was originally marketed by Armstrong as a “vacation city” with “mineral baths fed by artesian wells” (à la Hotel del Coronado in San Diego), the city ran into financial straits following the Panic of 1893 and lost the allure that had previously made it so desirable. As its population growth ossified, Oak Cliff made “numerous attempts” beginning in 1900 to annex itself into Dallas, and its calls were finally answered in 1903. On the other hand, the land that now comprises Highland Park was bought by Armstrong after the Panic of 1893 had already forced the Philadelphia Place Land Association, which originally bought the land in 1889, to cease its development and sell the property.

Even in its nascent years, Highland Park—named as such because of its location on high land overlooking downtown—functioned as a self-sustaining and largely independent community. Yet in 1913, it asked the city of Dallas to be annexed and was refused, so the 500 residents of Highland Park voted to incorporate separately and were granted rights in 1915. By then, Dallas had realized its mistake and battled the new city of Highland Park in court until 1945, when Highland Park turned Dallas’ annexation offers down for the last time.

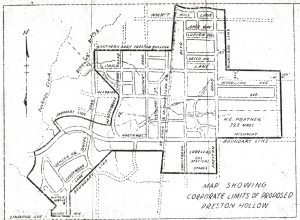

In the next decade, Highland Park came into its own as the premier suburb of Dallas, and its population took off, growing by 263% between 1920 and 1930. University Park, an adjacent suburb and home to Southern Methodist University (founded in 1915), also incorporated independent of the city of Dallas in 1924, when the university could no longer “afford to supply water and sewer lines” to the residential areas that housed its students and staff. The “Park Cities” collective success sparked further growth into the north, as Dallas’ Preston Hollow neighborhood experienced an influx of wealthy residents—entrepreneurs, doctors, industrialists, lawyers, and oil business people—who moved to the area in pursuit of the “triple dream”: a home, in a natural setting, with a community. The neighborhood’s great private schools (St. Mark’s School of Texas and Ursuline Academy) didn’t hurt either.

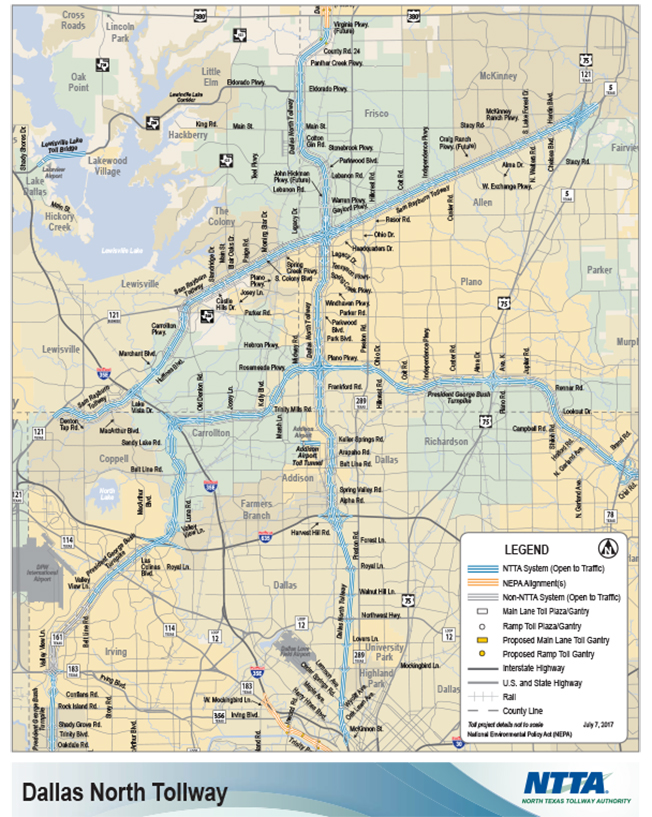

While the precedent of annexation resistance set by the Park Cities did not hold true for every north-bound city that came after it—Preston Hollow voted to become an annex in 1945, Addison incorporated separately in 1953—the Park Cities did succeed in moving most middle-upper class suburban growth north. Other factors like road construction also played a role in the development of this northward trend; although the Dallas North Tollway did not instigate the northward growth, it certainly reinforced it. Historically, real estate that surrounds major thoroughfares, be they streetcar lines, rivers or highways, is always more valuable than comparable real estate located farther away from thoroughfares. Thus following 1968 completion of the Tollway over the right-of-way that formerly accommodated the Cotton Belt Railroad, land values in the North Dallas area skyrocketed and incentivized even more northward growth. Dallas’ northern neighborhoods and suburbs were also often preferred to its southern counterparts by white, wealthy families, as the violence that occurred in South Dallas during the 1950’s as the city struggled with school integration, Civil Rights reforms, and its racially-troubled history—Dallas was home to the largest Ku Klux Klan chapter in Texas following WWI—was a deterrent for many prospective homebuyers.

Northward growth is as strong as ever in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, and it continues today at breakneck pace in cities like Frisco, Prosper, Allen, and McKinney. But there is no reason why we can’t change the tide. To follow this analogy, I propose that we put breakers in the ocean that is the Dallas metroplex so that we can keep the tide of urban growth within Dallas. Dallas Midtown is only the first chapter in this new narrative of back-to-the-city growth, and the sky is the limit when it comes to the number of districts we can revitalize—I actually believe that Dallas’ Fair Park district is an untapped market and has incredible potential. We must focus on building desirable communities and a strong tax base within the city of Dallas by emphasizing networks green space and attention to good urban form. Just as Snider Plaza and Highland Park Village set a precedent for shopping and entertainment in the 1930’s, I hope Dallas Midtown does the same for future development that pursue this new trend of South-bound growth. As I have said in previous blogs, Dallas is primed for a rubber band effect. Despite our north-bound focused history, there is no reason why we, as a city, cannot reverse the tide now.

Scott N. Beck

Scott N. Beck, a Dallas Texas Greenhill alumni, received a Masters of Accounting from the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin where he completed his B.B.A. Mr. Beck is a member of the Board of Directors of United Texas Bank and is President of Beck Ventures.

3 Comments

Leave a Reply

*

Maggie Sharer

August 9, 2017

I enjoy reading your informative blogs. Shared on Facebook with recommendation to sign up for them.

Russ Olivier

August 23, 2017

As a neighbor in this area I’d love to get behind this project, but since it was announced over 5 years ago I see little progress. This must be the slowest redevelopment in the history of Dallas, and I fear the booming real estate cycle will end before this project even truly starts. Meanwhile the area continues to decline and crime continues to rise. I see a lot of positive press coverage but no one is asking the tough questions .. why is this taking so long? I know the project is complicated and have heard all of those excuses. But I see what’s happening in Plano and Frisco at lightening speed compared to this project. I know demolition of the mall has supposedly started, but I fear this was just to meet the city deadlines imposed … if you go by now, the demolition has basically stopped (or is at such a snail’s pace that it’s hard to tell!). I think the neighborhood, which was so excited and supportive of this effort when it was announced, is loosing its patience. I know I am.

Fresh Yacon Root

October 30, 2017

I enjoy looking through your blog. It was amazingly exciting. 🙂